5. Use of Thrust: Thrust Force Along Velocity Vector¶

This example focuses on the inclusion of a thrust force in Tudat. In this example, the dynamics of the inner solar system (Sun, Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Moon) is simulated. The code for this tutorial is given here on Github, and is also located in your tudat bundle at:

tudatBundle/tudatExampleApplications/satellitePropagatorExamples/SatellitePropagatorExamples/thrustAlongVelocityVectorExample.cpp

Although thrust is in principle handled just like any other force and Tudat, you as a user have much more control over how this thrust behaves. In fact, optimizing the thrust profile is an important goal of many types of simulations. The addition of a thrust force requires the addition of the following blocks of code/information:

- Definition of thrust direction/magnitude, in many cases as a function of time (or other variables).

- Definition of specific impulse, in some cases as a function of time (or other variables).

- Inclusion of vehicle mass in the state vector: using thrust decreases the mass of the spacecraft, which we propagate concurrently with the translational state.

A list of options/details of the first two of these points is discussed here. For the example here, we will only treat a single type of thrust model, for which:

- The thrust force and specific impulse are constant.

- The direction of the thrust is always along (and in the same direction as) the vehicle’s Earth-centered velocity vector.

We will not treat the entire source file for the simulation, as most of it is similar or identical to that discussed in detail in Unperturbed Earth-orbiting Satellite and Perturbed Earth-orbiting Satellite.

5.1. Adding the thrust acceleration¶

The first main difference w.r.t. the other examples is the use of a thrust acceleration. For this example, the full code required for this is:

// Define thrust settings double thrustMagnitude = 25.0; double specificImpulse = 5000.0; boost::shared_ptr< ThrustDirectionGuidanceSettings > thrustDirectionGuidanceSettings = boost::make_shared< ThrustDirectionFromStateGuidanceSettings >( "Earth", true, false ); boost::shared_ptr< ThrustEngineSettings > thrustMagnitudeSettings = boost::make_shared< ConstantThrustEngineSettings >( thrustMagnitude, specificImpulse ); // Define acceleration model settings. std::map< std::string, std::vector< boost::shared_ptr< AccelerationSettings > > > accelerationsOfVehicle; accelerationsOfVehicle[ "Vehicle" ].push_back( boost::make_shared< ThrustAccelerationSettings >( thrustDirectionGuidanceSettings, thrustMagnitudeSettings) );

First, we define a constant thrust force of 25 N and specific impulse of 5000 s. For the interface of the thrust we use here, two blocks need to be defined before creating the AccelerationSettings, one providing settings for the direction, and one for the magnitude of the thrust force.

The direction settings are defined by an object of type (derived from) ThrustDirectionGuidanceSettings. For this example, we use a derived class designed specifically to set the thrust in the direction of the vehicle velocity vector. Please go to Thrust Guidance for the other options for the direction settings:

boost::shared_ptr< ThrustDirectionGuidanceSettings > thrustDirectionGuidanceSettings = boost::make_shared< ThrustDirectionFromStateGuidanceSettings >( "Earth", true, false );

The three input arguments to the constructor of the ThrustDirectionFromStateGuidanceSettings represent:

- The central body w.r.t. which the velocity is to be computed when setting the thrust direction. For instance, the propagation of a vehicle may be done w.r.t. the Sun, while the thrust direction is computed from the velocity w.r.t. the Earth.

- Whether the thrust is colinear with velocity (true) or position (false) w.r.t. the central body.

- Whether the thrust force is in the same direction (false), or opposite to the direction (true), of the state of the vehicle w.r.t. the central body.

We have set the thrust force to be in line and in the same direction as the velocity vector of the spacecraft w.r.t. the Earth. Defining the magnitude of the thrust (and specific impulse) is done through the dedicated derived class ConstantThrustEngineSettings:

boost::shared_ptr< ThrustEngineSettings > thrustMagnitudeSettings = boost::make_shared< ConstantThrustEngineSettings >( thrustMagnitude, specificImpulse );

with the first and second arguments of the ConstantThrustEngineSettings representing the constant thrust force and specific impulse. Now, the thrust acceleration settings are added to the accelerationsOfVehicle list as follows:

accelerationsOfVehicle[ "Vehicle" ].push_back( boost::make_shared< ThrustAccelerationSettings >( thrustDirectionGuidanceSettings, thrustMagnitudeSettings) );

where you can see that defining a thrust acceleration requires a dedicated derived class of AccelerationSettings. This derived class ThrustAccelerationSettings takes the settings for the magnitude and direction of the thrust force, which we just created, as input. A final point to remember when defining the ThrustAccelerationSettings is that thrust is a force that the vehicle exerts on itself.

5.2. Propagating the mass and the orbit¶

For consistent simulation results, the mass decrease as a result of the expelled propellant must be included in the simulation. Doing so requires a significant modification of the way in which the propagator settings are defined. The total block of code is:

// Define propagation termination conditions (stop after 2 weeks). boost::shared_ptr< PropagationTimeTerminationSettings > terminationSettings = boost::make_shared< propagators::PropagationTimeTerminationSettings >( 14.0 * physical_constants::JULIAN_DAY ); // Define settings for propagation of translational dynamics. boost::shared_ptr< TranslationalStatePropagatorSettings< double > > translationalPropagatorSettings = boost::make_shared< TranslationalStatePropagatorSettings< double > > ( centralBodies, accelerationModelMap, bodiesToPropagate, systemInitialState, terminationSettings, cowell ); // Create mass rate models boost::shared_ptr< MassRateModelSettings > massRateModelSettings = boost::make_shared< FromThrustMassModelSettings >( 1 ); std::map< std::string, boost::shared_ptr< basic_astrodynamics::MassRateModel > > massRateModels; massRateModels[ "Vehicle" ] = createMassRateModel( "Vehicle", massRateModelSettings, bodyMap, accelerationModelMap ); // Create settings for propagating the mass of the vehicle. std::vector< std::string > bodiesWithMassToPropagate; bodiesWithMassToPropagate.push_back( "Vehicle" ); Eigen::VectorXd initialBodyMasses = Eigen::VectorXd( 1 ); initialBodyMasses( 0 ) = vehicleMass; boost::shared_ptr< PropagatorSettings< double > > massPropagatorSettings = boost::make_shared< MassPropagatorSettings< double > >( bodiesWithMassToPropagate, massRateModels, initialBodyMasses, terminationSettings ); // Create list of propagation settings. std::vector< boost::shared_ptr< PropagatorSettings< double > > > propagatorSettingsVector; propagatorSettingsVector.push_back( translationalPropagatorSettings ); propagatorSettingsVector.push_back( massPropagatorSettings ); // Create propagation settings for mass and translational dynamics concurrently boost::shared_ptr< PropagatorSettings< double > > propagatorSettings = boost::make_shared< MultiTypePropagatorSettings< double > >( propagatorSettingsVector, terminationSettings );

The first line explicitly creates the object defining the termination conditions of the propagation.

boost::shared_ptr< PropagationTimeTerminationSettings > terminationSettings = boost::make_shared< propagators::PropagationTimeTerminationSettings >( 14.0 * physical_constants::JULIAN_DAY );

This is similar to the step we took in a previous example, but distinct from the first two examples, where we simply passed the final time variable as a double to the constructor of our propagation settings. Please go to Propagator Settings: Termination Settings for further details on termination settings.

In the next step, we create the propagation settings for the translational dynamics, in the same way as is done in the previous examples. To incorporate the change in vehicle mass, we need to create mass rate models, which are essentially the equivalent of accelelations for ‘mass dynamics’. They compute the time derivative of the mass at each time step. Defining the settings for these models is done by creating objects of class (derived from) :class`MassRateModelSettings`, analogously how acceleration settings are defined by AccelerationSettings objects. The following code is used to create the mass rate models:

// Create mass rate models boost::shared_ptr< MassRateModelSettings > massRateModelSettings = boost::make_shared< FromThrustMassModelSettings >( true ); std::map< std::string, boost::shared_ptr< basic_astrodynamics::MassRateModel > > massRateModels; massRateModels[ "Vehicle" ] = createMassRateModel( "Vehicle", massRateModelSettings, bodyMap, accelerationModelMap );

For our example, we want to derive the mass rate models from the thrust acceleration on Vehicle. To this end, our mass rate model settings are of type FromThrustMassModelSettings. Please go to Mass rate model setup for the available mass rate model settings. You may wonder why we are passing the value true to the constructor of this class. This is done to specify that the mass rate model should include expelled propellant due to all thrust forces acting on the body (for this example this makes no difference, but may be relevant for more detailed simulations).

The next step is to create the full settings for the propagation of the mass. Just like for the propagation of the dynamics, we create an object of a type (derived-from) PropagatorSettings. For mass rate, this type is MassPropagatorSettings. It requires as input:

- List of bodies for which the mass is to be propagated.

- Mass rate models for these bodies.

- The initial masses of the bodies (stored in a Eigen::VectorXd).

- Settings for when to terminate the propagation.

Below, you can see how these settigns are passed to the MassPropagatorSettings constructor.

// Create settings for propagating the mass of the vehicle. std::vector< std::string > bodiesWithMassToPropagate; bodiesWithMassToPropagate.push_back( "Vehicle" ); Eigen::VectorXd initialBodyMasses = Eigen::VectorXd( 1 ); initialBodyMasses( 0 ) = vehicleMass; boost::shared_ptr< PropagatorSettings< double > > massPropagatorSettings = boost::make_shared< MassPropagatorSettings< double > >( bodiesWithMassToPropagate, massRateModels, initialBodyMasses, terminationSettings );

Our final step is to tell the software to propagate both the translational dynamics and body mass, which is achieved as follows:

// Create list of propagation settings. std::vector< boost::shared_ptr< PropagatorSettings< double > > > propagatorSettingsVector; propagatorSettingsVector.push_back( translationalPropagatorSettings ); propagatorSettingsVector.push_back( massPropagatorSettings ); // Create propagation settings for mass and translational dynamics concurrently boost::shared_ptr< PropagatorSettings< double > > propagatorSettings = boost::make_shared< MultiTypePropagatorSettings< double > >( propagatorSettingsVector, terminationSettings );

As is discussed in more detail in Create a Dynamics Simulator Object. This PropagatorSettings object, which contains settings for both translational dynamics and mass rate, can be passed to the SingleArcDynamicsSimulator in the exact same manner as was done in the previous examples.

5.3. Results¶

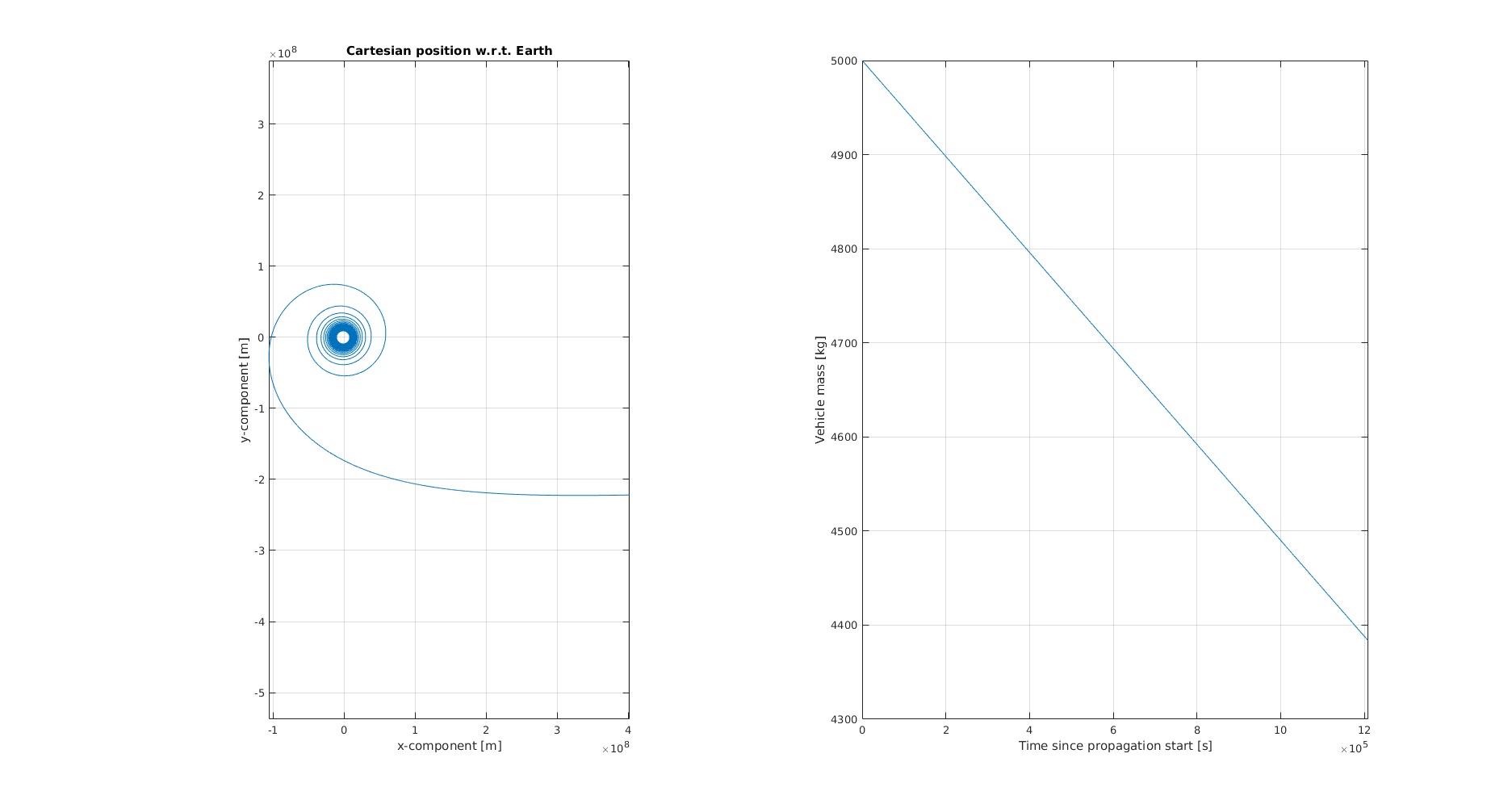

Below, you see the (in-plane) resulting dynamics of the spacecraft and the mass of the vehicle as a function of time. The thrust force is along the velocity vector, constantly adding kinetic energy to the spacecraft. As a result, you can see the orbit slowly spiral outwards. Since the specific impulse and thrust force were both set to a constant value, the body mass decreases exactly linearly.

Tip

Open the figure in a new tab for more detail.