6. Use of Thrust: User-defined Thrust Vector¶

In the previous tutorial, we discussed how to include thrust in a simulation, separately specifying the direction and magnitude of the thrust force. Alternatively, however, you may want to impose the thrust vector (direction and magnitude in some reference frame) as a function of time explicitly. In this tutorial, we will look at which Tudat interfaces you can use to accomplish this. The code for this tutorial is given here on Github, and is also located in your tudat bundle at:

tudatBundle/tudatExampleApplications/satellitePropagatorExamples/SatellitePropagatorExamples/thrustAccelerationFromFileExample.cpp

The main difference of this example w.r.t. the previous one lies in the following steps:

- Loading discrete thrust data from a file.

- Creating an interpolator that turns the discrete data set into a continuous function.

- Creating settings for the thrust acceleration using these data.

6.1. Loading the data¶

Reading data from a file can be done in many different ways. Since the manner in which a file is read depends on the structure of the particular file, there can be many different approaches (and file readers) for different applications. Here, we chose a very basic setup in which the thrust file is set up as follows:

0 0 0 5

6068 0 1 5

6097 1.0 0 5

6097.5 0.8 0 5

6098 0.6 0.1 5

6099 0.1 0.5 5

12192 0.2 1.0 4.5

18288 0.3 1.5 4.0

243575 0.4 2.0 3.0

3.999e6 1.0 1.0 2.0

4e6 1.1 5.0 1.0

The first column of this file represents a time, the following three columns represent the x-, y- and z-components of the thrust force vector. To load these data into Tudat, we use the following custom function:

std::map< double, Eigen::Vector3d > getThrustData( )

{

// Find filepath and folder of this cpp file

std::string cppFilePath( __FILE__ );

std::string cppFolder = cppFilePath.substr( 0 , cppFilePath.find_last_of("/\\")+1 );

// Load data into matrix

Eigen::MatrixXd thrustForceMatrix =

tudat::input_output::readMatrixFromFile( cppFolder + "testThrustValues.txt" , " \t", "#" );

// Fill thrustData map using thrustForceMatrix Eigen matrix

std::map< double, Eigen::Vector3d > thrustData;

for ( int i = 0; i < thrustForceMatrix.rows( ); i++ )

{

Eigen::Vector3d temp = thrustForceMatrix.block( i, 1, 1, 3 ).transpose( );

thrustData[ thrustForceMatrix( i, 0 ) ] = temp;

}

return thrustData;

}

First, we need to specify the location of the file we wish to load. To do this, we retrieve the string containing the current file (e.g. the .cpp file with the source code of the example) as follows:

std::string cppFilePath( __FILE__ );

Subsequently, we strip of the name of the current file as follows:

std::string cppFolder = cppFilePath.substr( 0 , cppFilePath.find_last_of("/\\")+1 );

Don’t worry if the details of these steps escape you. What is important is to know that the cppFolder now contains the location of the current directory. We now load the data into an Eigen::MatrixXd using a Tudat function readMatrixFromFile, located in InputOutput/matrixTextFileReader.cpp as follows:

// Load data into matrix

Eigen::MatrixXd thrustForceMatrix =

tudat::input_output::readMatrixFromFile( cppFolder + "testThrustValues.txt" , " \t" );

The first argument to the readMatrixFromFile denotes the full file location of our testThrustValues.txt file containing the thrust data. The second argument: ” t” denotes that both spaces and tabs (t) are considered separators for the file contents (points in the file where a new entry starts). To use the interpolator, we want to have our thrust data in a std::map, with the time as key and thrust vector as value. The following block of code converts the Eigen::MatrixXd to a std::map< double, Eigen::Vector3d >:

// Fill thrustData map using thrustForceMatrix Eigen matrix

std::map< double, Eigen::Vector3d > thrustData;

for ( int i = 0; i < thrustForceMatrix.rows( ); i++ )

{

thrustData[ thrustForceMatrix( i, 0 ) ] = thrustForceMatrix.block( i, 1, 1, 3 ).transpose( );

}

return thrustData;

6.2. Creating the interpolator¶

We now have a std::map with time vs. thrust force. To pass this information to the AccelerationSettings, we need to turn this discrete data into a continuous function, for which we use an interpolator. Here, we choose to use a linear interpolator. For a list of the various other interpolation options, details of their implementation, and instructions on how to use/create them, go to Interpolators. For this example, we use the following code to create an interpolator of the thrust vector:

// Retrieve thrust data as function of time.

std::map< double, Eigen::Vector3d > thrustData = getThrustData( );

// Make interpolator

boost::shared_ptr< InterpolatorSettings >

thrustInterpolatorSettingsPointer = boost::make_shared< InterpolatorSettings >( linear_interpolator );

// Creating settings for thrust force

boost::shared_ptr< OneDimensionalInterpolator< double, Eigen::Vector3d > >

thrustInterpolatorPointer = createOneDimensionalInterpolator< double, Eigen::Vector3d >(

thrustData, thrustInterpolatorSettingsPointer );

The first line reads the std::map from the file we have specified. The following part:

// Make interpolator

boost::shared_ptr< InterpolatorSettings >

thrustInterpolatorSettingsPointer = boost::make_shared< InterpolatorSettings >( linear_interpolator );

creates an object InterpolatorSettings that contains the settings for how to create the interpolator. For this application, this means specifying that the interpolator should be of the type linear_interpolator. Note that this setup is very similar to how an environment/acceleration/etc. model is set up.

The interpolator is then created by calling:

// Creating settings for thrust force

boost::shared_ptr< OneDimensionalInterpolator< double, Eigen::Vector3d > >

thrustInterpolatorPointer = createOneDimensionalInterpolator< double, Eigen::Vector3d >(

thrustData, thrustInterpolatorSettingsPointer );

The OneDimensionalInterpolator object is created using the thrustData and thrustInterpolatorPointer defined above. The first parameter of the OneDimensionalInterpolator denotes that the independent variable is a double (time) and the dependent variable is a Eigen::Vector3d (thrust).

6.3. Creating the thrust acceleration.¶

The creation of the thrust acceleration is done similarly as in the previous example, by creating an object of type ThrustAccelerationSettings, as follows:

double constantSpecificImpulse = 3000.0;

accelerationsOfVehicle[ "Vehicle" ].push_back(

boost::make_shared< ThrustAccelerationSettings >(

thrustInterpolatorPointer,

boost::lambda::constant( constantSpecificImpulse ), lvlh_thrust_frame, "Earth" ) );

The input to the ThrustAccelerationSettings, however, is different from that used in the previous example. In fact, we use a different constructor here, an example of constructor overloading. The input required to the constructor we use here is:

- The interpolator used to compute the thrust force vector as a function of time.

- Function returning the specific impulse as a function of time (here constant at the 3000 s). If you are not familiar with

boost::lambda::constant, have a look here.- The frame type in which the thrust vector is expressed.

- The reference body for any frame transformation that may be required.

The last two argument define the frame orientation in which the thrust force produced by the thrustInterpolatorPointer is expressed. At present, there are two options:

- Inertial frame: if this is the case, there is no need to specify a reference body. The interpolated thrust is used directly in the equations of motion, without and transformation.

- Local-Vertical Local-Horizontal. This is a satellite-based frame in which the x-axis is colinear and in the direction of the velocity vector (relative to the reference body). The z-axis is perpendicular to the orbital plane (direction of cross-product of velocity with postion) and the y-axis completes the system.

In this example, we use the second option, basing the thrust direction on the current Earth-centered position of the spacecraft.

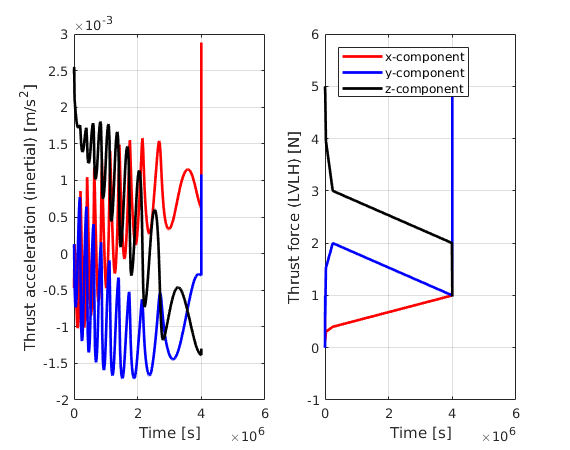

The rest of the application, including the definition of the mass propagation, is set up analogously to the previous example, with a single addition: two dependent variables are saved during the propagation, the thrust acceleration, and the rotation matrix from LVLH to inertial frame. Note that when saving an acceleration, it is always saved as expressed in the inertial frame. We also save the rotation matrix here, to reconstruct the original thrust profile that we provided, checking the correct implementation.

6.4. Results¶

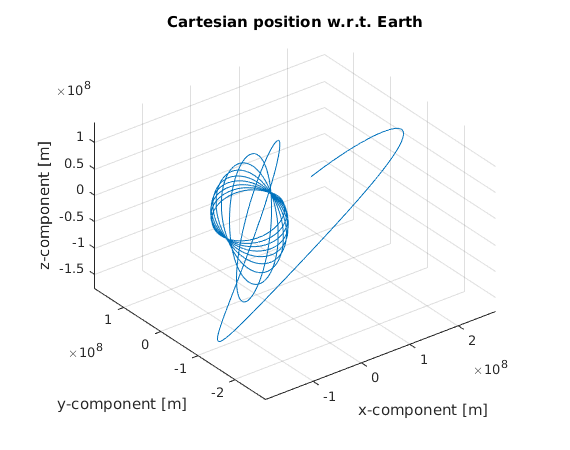

Below, we show the resulting orbit of the spacecraft w.r.t. the Earth. Clearly, the thrust force that we apply has a significant effect, changing the orbital plane and increasing the spacecraft’s mean distance from the Earth.

We also show plots of the acceleration (in an inertial frame) and force (in the LVLH frame) due to the thrust. The thrust profile clearly shows the linearly interpolated behaviour from our input data. For the acceleration, the once-per-orbit signature of the transformation is clearly visible.